Evolving Dynamics in Public Opinion: Polling Trust, Partisan Cooperation, and Election Skepticism

Chapter 1: Poll-arization: Expert Perceptions and Public Realities of Trust in Polling

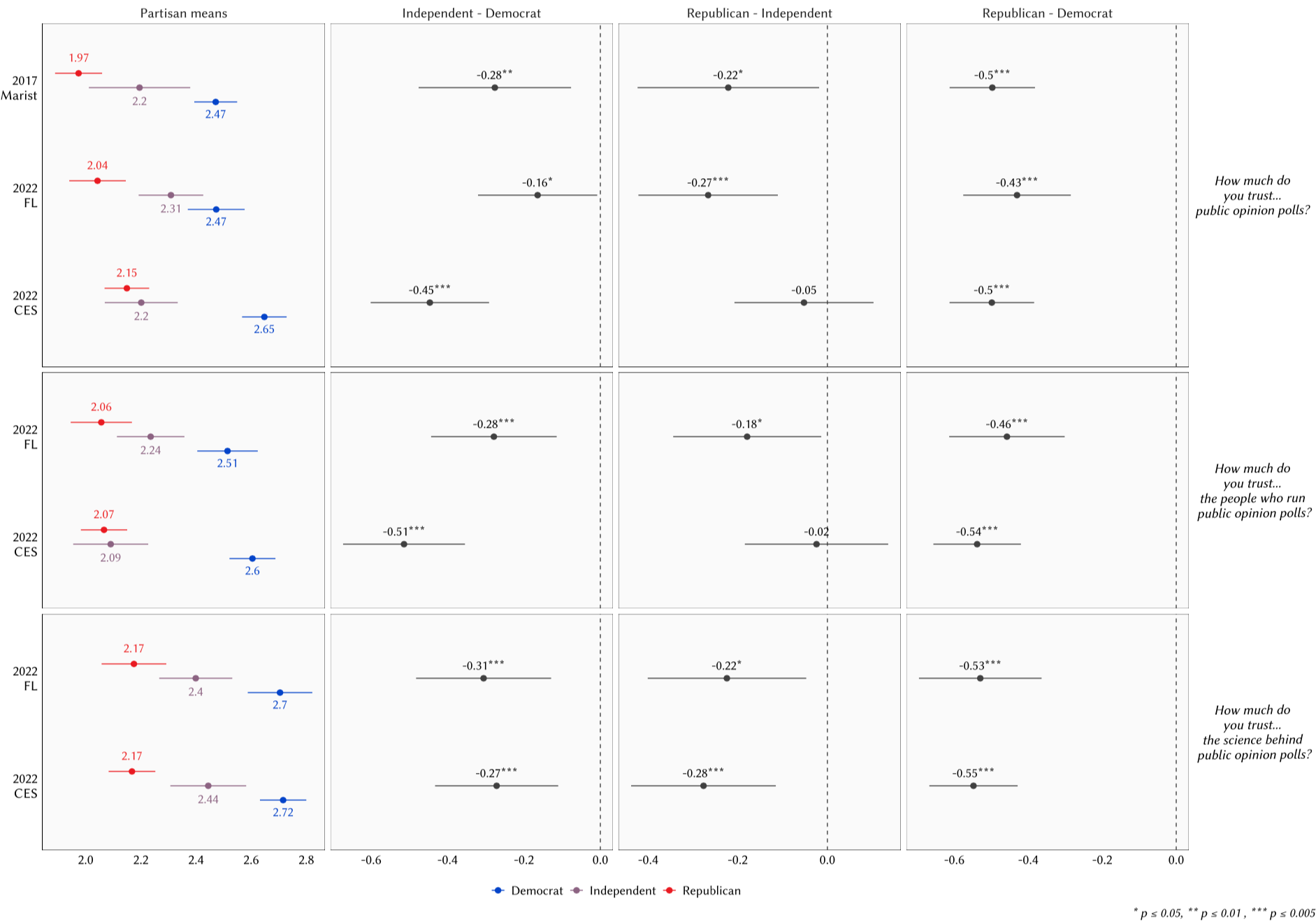

The apparent “failures” of recent pre-election polls and election forecasts have resulted in prominent political voices casting doubt on polls and speculating that public trust in polling has decreased, particularly among Republicans. The degree to which experts subscribe to this narrative is unknown, and contemporary evidence on public and subgroup trust in polling has been scarce. This paper updates our understanding of both experts and the public by examining an original expert survey as well as five public opinion surveys spanning multiple decades. While aggregate trust has remained stable since the early 2010s, older individuals, Republican partisans, and conservatives consistently report lower trust. Additionally, I find no association between polling trust and whether citizens participated in the 2022 primary and general elections. These results underscore the value of routinely benchmarked attitudinal metrics in the public and reveal recent partisan cleavages in polling trust.

Chapter 3: AI-Supplemented Corrections Improve Accuracy and Confidence among Election Skeptics (co-authored with Katie R. Gouge, Ryan P. Kennedy, and Thomas J. Wood)

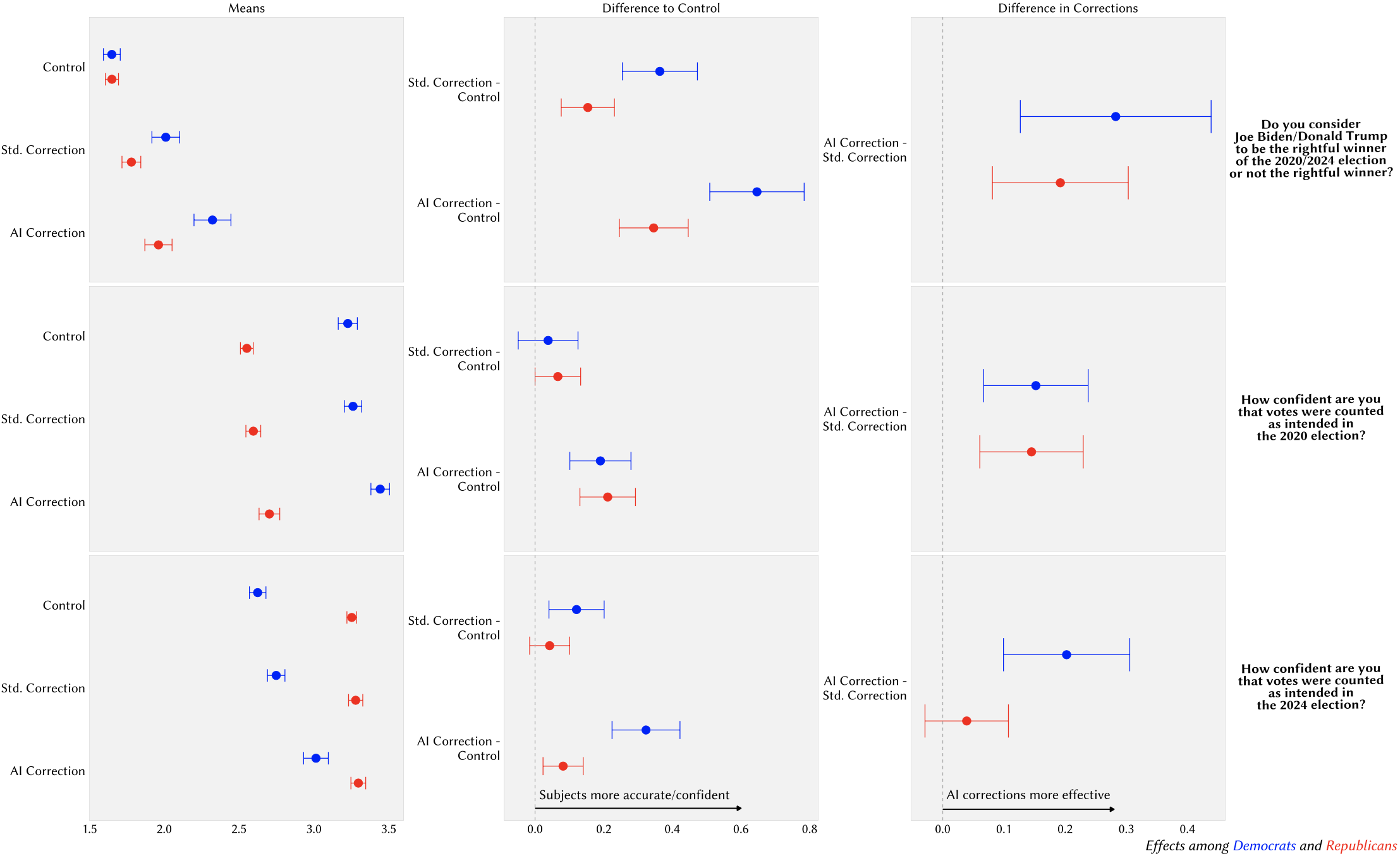

Corrective interventions have repeatedly been shown to be improve accuracy when targeting specific misinformed beliefs, but they tend to have minimal or no impact on related attitudes or behaviors (Porter and Wood, 2024; Carey et al., 2025). Separately, the use of AI as an information source continues to increase among Americans. This study investigates the efficacy of employing AI as a supplement to traditional corrections on both beliefs and attitudes related to the accuracy and integrity of American elections. Among a sample of election skeptics (n = 1,621), we added an AI chatbot component to a standard correction and test the effect on specific misinformed beliefs about presidential winners, as well as on confidence in the 2020 and 2024 vote counts. Both corrections yield increased factual accuracy regarding presidential winners, with the AI correction providing greater accuracy increases relative to standard corrections alone. Additionally, both the standard correction and the AI correction increased confidence, but only in evaluations of 2024 vote counts. Belief effects persisted two weeks post-treatment, while confidence effects decayed in the interim (n = 1,066). As AI continues to proliferate, these results indicate its potential to help improve accuracy and bolster confidence among those who express doubt in American election outcomes and processes.

Chapter 2: Vibe Check: How Political Context Shapes Partisan Survey Participation

Political polls and surveys have historically provided a critical window into public opinion. However, recent studies suggest that survey participation is increasingly shaped by political engagement and partisan asymmetries (Cavari and Freedman, 2023; Clinton, Lapinski and Trussler, 2022). While some scholars attribute these patterns to electoral context (Gelman et al., 2016; Borgschulte, Cho and Lubotsky, 2022) others find no systematic difference based on partisanship (Hopkins and Gorton, 2024). I propose that partisan differences in survey participation are not influenced by election-related factors alone (such as campaign activity or media coverage), but also follow a distinct time-based pattern that aligns with which party controls the presidency, moderated by the president's approval rating. When a Democrat is in office, Democratic respondents may be more likely to cooperate with surveys, while Republican respondents may disengage (and vice versa). Moreover, partisans may respond to shifts in presidential approval by opting in (or out) of surveys when the president has positive (or negative) approval among the general public. Leveraging over 100 waves of Pew’s American Trends Panel (2014–2023) and over 1,900 estimates of presidential approval from public opinion polls archived by the Roper Center at Cornell University, I anticipate evidence of differential partisan cooperation. Specifically, I expect heightened response rates among co-partisans of the sitting president, with pronounced increases following general elections and modest fluctuations during dips (and spikes) in presidential approval.